The Abbey of St Clare and Goodman's Fields

Franciscan nuns, or Poor Clares, were established at the House of Minoresses in Aldgate in 1293, by the brother of Edward I, Edmund, Duke of Lancaster, brother of Edward I, in 1293. The first sisters were brought to England by his wife, Blanche of Navarre, probably from France. The sisters were not wealthy but were granted privileges by the King and the Pope, which gave them considerable freedom. The House was endowed with various plots of land, rents and tenements in London and further afield during the 13th century. The House of Minoresses was priviliged. They were, for example, exempt from paying tax, and were beyond the control of bishops. They were also beyond the reach of the law, with the exception of ‘treason or felony touching our crown’. in that it was exempt from

summonses before the justices in eyre for common pleas and pleas of the forest by the king. The pope, Boniface VIII, ordered that nothing should be exacted from them for the consecration of church and altars, or for sacred oil or sacraments, but that the bishop of the diocese should perform these offices free of charge; that in a general interdict they might celebrate service with closed doors; that sentences of excommunication and interdict promulgated against them by bishops or rectors should be of no effect, and he declared them free from all jurisdiction of the archbishop of Canterbury and of the bishop of London, and acquitted them of payment of tenths to the pope.

Excerpt from British History Online

Edmund died in 1296 and his heart was buried under the high altar. Many significant medieval figures, particularly women, were buried within the confines of the convent. These included in 1360 Elizabeth de Burgh, Countess of Clare and founder of Clare College Cambridge; and Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York and wife of the younger prince murdered in the Tower, buried here in 1481. Anne’s coffin was discovered in 1964 and transferred to Westminster Abbey. The House attracted the widows and daughters of powerful people, including the family of the Duke of Gloucester, all of whom endowed and granted further privilidges and lands to the House during the 14th and 15th centuries.

In 1515, 27 of the nuns died of infection and shortly after the outbreak of plague, the convent buildings were destroyed by fire. The rebuilding of the House of Minoresses was aided by contributions from the mayor, aldermen, and citizens of London to the sum of 200 marks but at the special request of Cardinal Wolsey to the Court of Common Council, it was decided in 1520 to give 100 marks more to complete the building. The king donated £200.

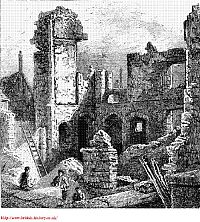

After the Dissolution, the nunnery was surrendered to Henry VIII by the last abbess, Dame Elizabeth Salvage, in 1539, who was subsequently granted a pension of £40, and the nunnery became the residence of John Clark, Bishop of Bath and Wells, Henry VIII’s ambassador to the Duke of Cleve.

It seems probable, from documentary evidence, that a farm on the Prescot Street site was run by the convent and produced both food and income. A farmer and labourers were employed. Gradually this arrangement changed to a tenancy, and before the suppression of the monasteries the earliest recorded tenant farmer of the land was a man called Trollope, and then sold to a farmer Goodman. After the Dissolution the farm became known as Goodman’s Fields, the name by which the site continued to be known for some three hundred years.

The farm kept some 30 to 40 head of cattle and was still flourishing in 1601 when the historian John Stowe visited. John Stowe wrote in the 16th century:

Near adjoining to this abbey, on the south side thereof, was sometime a farm belonging to the said nunnery; at the which farm I myself in my youth have fetched many a halfpenny worth of milk, and never had less than three ale pints for a halfpenny in the summer, nor less than one ale quart for a halfpenny in the winter, always hot from the kine, as the same was milked and strained. One Trolop, and afterwards Goodman, were farmers there, and had thirty or forty kine to the pail. Goodman’s son being heir to his father’s purchase, let out the ground first for the grazing of horses, and then for garden-plots, and lived like a gentleman thereby.

Clearly the pasture here was rich. However Mr Goodman’s descendants and successors intended to raise themselves above the farming classes. Mr Goodman’s son and heir – known only as another ‘Mr Goodman’ let this great field to a variety of small tenants, firstly as grazing for horses, then for garden-plots and smallholdings, and is said to have lived ‘like a gentleman’ on the proceeds. By 1678, the land was beginning to to be sold off for the construction of housing.

- Author: Lorna Richardson |

- Aug 01, 2008

- Share